Ethnic diversity in fertility treatment 2021

Preliminary UK ethnicity statistics for IVF and DI treatment, storage, and donation

Published: December 2023

Download the underlying dataset as .xlsx

Table of contents

- Main points

- Introduction

- Note on preliminary and ethnicity data

- Section 1. IVF birth rates increased across all ethnic groups, though disparities remain

- Section 2. Black patients started fertility treatment later than other ethnic groups

- Section 3. DI predominantly used by White patients

- Section 4. Imported donor sperm and eggs vary by ethnicity

- Section 5. Multiple birth rate decreased in all ethnic groups, but remain highest for Black patients

- Section 6. Use of egg storage was similar across all ethnic groups

- Section 7. Higher proportions of Black patients were single

- Section 8. NHS-funded IVF cycles declined most among Black patients

- Conclusion and next steps

- About our data

Main points

- This report highlights disparities in use and outcomes of fertility treatment in the UK by ethnic group from 2017-21.

- Average in vitro fertilisation (IVF) birth rates increased across all ethnic groups, but Black patients had lower IVF birth rates. For Black patients aged 18-37, the average IVF birth rate per embryo transferred using fresh embryo transfers was on average 23%, compared to 32% for White patients in 2020-21.

- Average age at starting treatment, a key factor in success rates, was higher among Black patients in heterosexual couples at 36.0 years of age, compared to the national average of 35.0 in 2021.

- Female same-sex couples started fertility treatment at 32.7 years on average, while Asian patients with a female partner were older at 35.8 years in 2017-21.

- Asian and Black single patients started fertility treatment at 38-39 years on average, compared to an average age of 36.2 years for White single patients in 2017-21.

- Donor insemination (DI) was predominantly used by White patients, accounting for 92% of DI patients in 2017-21, compared to 2% for Black patients.

- Asian patients represented a larger proportion of IVF patients at 15%, but a smaller proportion of DI patients at 3% in 2017-21, compared to 11% of an age-matched UK population.

- Over half of sperm used in treatment from donors of Mixed, Other and Black backgrounds in 2017-21 was imported from abroad.

- Multiple birth rates declined in all ethnic groups, but Black patients continued to have the highest rates at 9%, compared to 7% for White patients in 2017-21.

- Use of egg storage cycles was similar across ethnic groups with egg storage accounting for 3% of all cycles on average in 2017-21.

- Black patients were more commonly single compared to other ethnic groups, with 6% of Black IVF patients and 62% of Black DI patients being single in 2017-21.

- IVF cycles funded by the National Health Service (NHS) declined most among Black patients in heterosexual couples, decreasing from 60% in 2019 to 41% in 2021, compared to a decrease from 66% to 53% among White patients.

- In 2017-21, 12% of patients under 40 in female same-sex relationships received NHS-funded IVF or DI cycles, ranging from 12% for White patients to 6% for patients with a mixed background.

Introduction

This report follows our first publication on ethnic diversity in fertility treatment in 2021, looking at how use of fertility treatments and outcomes of fertility treatment, differed by ethnic group. Key actions to reduce these disparities were identified in the previous report and updates of these are summarised in the concluding section, along with a call to action to reduce disparities in access to and outcomes for Black, Asian and ethnic minority patients.

Ethnic comparisons are limited by the data we hold on our Register and there are a number of factors that may relate to the differences we outline in this report, such as social, economic and structural factors which have been shown to contribute to ethnic disparities in health in the United Kingdom (UK). We do not hold this information on our Register and therefore could not account for these differences in any comparisons drawn.

Where possible we have added in broad interpretations of why disparities may exist and have included references to peer-reviewed academic or other publications that provide further information.

Note on preliminary and ethnicity data

This report provides data on fertility treatment and outcomes in the UK from 2008 to 2021 available on the HFEA data Register. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and large-scale work to upgrade the HFEA data submission system and migrate data to a new database, data on treatments and pregnancies from 2020-21 and outcomes from 2019-21 have not yet been validated. This means that some data in this report is preliminary and cannot be compared to other reports.

Classification of ethnicity used throughout this report is based on the 2021 Census for England and Wales.1 Around 13% of patients in 2017-21 were excluded in this report due to unreported ethnicity data. Due to changes in ethnicity classification, the data in this report cannot be directly compared to our publications on ethnicity prior to early 2023. See the Quality and Methodology report for more information.

Five aggregated ethnic categories have been used throughout this report (Asian, Black, Mixed, White and Other – as used in the 2021 Census of England and Wales1) to allow for more reliable comparisons across ethnicities due to increased numbers. These aggregated categories encompass a wide range of ethnicities. However, differences may exist within the categories and some data is available on more detailed ethnic categories in the underlying dataset. Where the numbers in a single year are too small for robust estimates by ethnicity, we have aggregated the data by up to five years.

This report focuses mainly on ethnicity of patients, further information on ethnicity of partners is provided in the underlying dataset.

1. IVF birth rates increased across all ethnic groups, though disparities remain

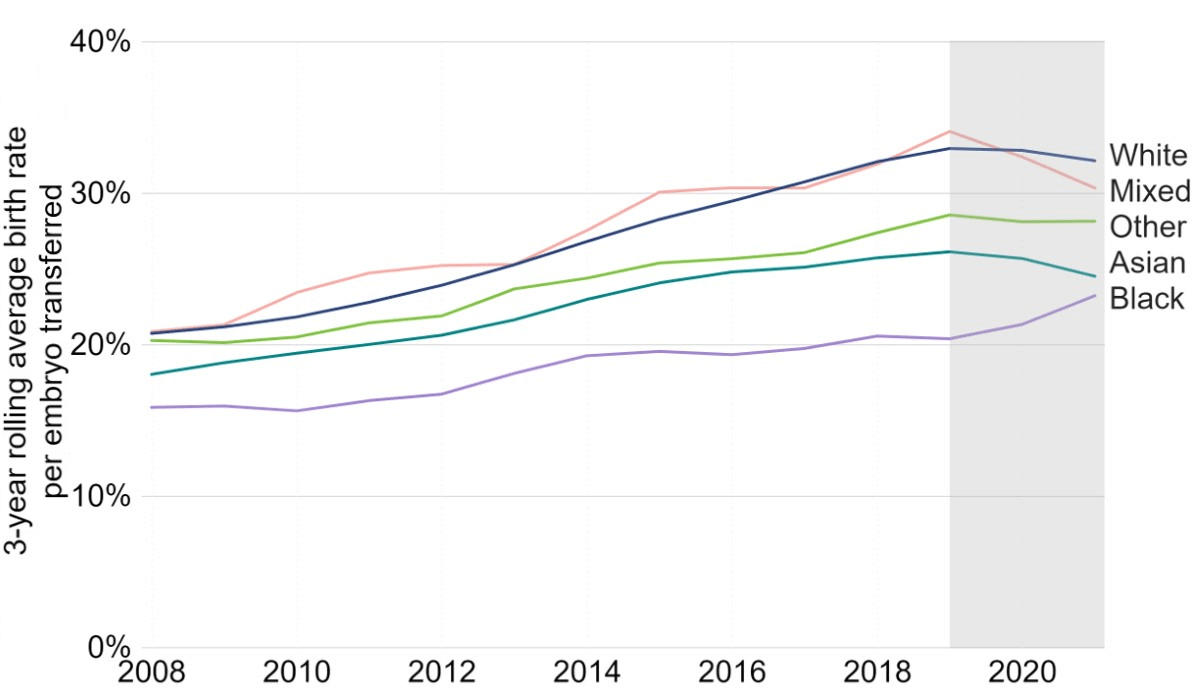

The average IVF birth rate per embryo transferred has increased across all ethnic groups (Figure 1). However, Black and Asian patients consistently had the lowest birth rates. In 2021, the average IVF birth rate using fresh embryo transfers among patients aged 18-37 was 23% for Black patients and 24% for Asian patients. White patients had the highest rate of 32%.

These findings are consistent with previous studies in the UK and United States.2,3 The reasons for these variations are not certain but may relate to other differences across ethnicities, ranging from age at treatment, reproductive and underlying general health conditions to social, economic and structural factors.4 See Figure 2 for information on ethnic differences in birth rates by age.

Figure 1. IVF birth rates increased across all ethnic groups, but disparities remain

Three-year rolling average fresh embryo transfer IVF birth rate per embryo transferred using patient eggs among patients aged 18-37 by ethnicity, 2008-21 (preliminary 2019-21 data)

Note figure 1: Birth rates for 2019, 2020 and 2021 are preliminary and have not been validated (grey band). This data includes IVF treatment cycles using their own egg and fresh embryo transfers, and begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. Treatments using PGT-A/M/SR, donor eggs or surrogacy, and treatments in which a pregnancy was recorded and no birth outcome recorded have been excluded. A three-year rolling average (the average of the previous, current and following years) for 2009-2020 and two-year rolling average for 2008 and 2021 was used to present birth rates to provide an indication of trends without yearly variations due to low numbers per year in some ethnic groups. Birth rates per year are provided in the underlying dataset. Decreases in IVF birth rates between 2019 and 2021 are likely due to missing outcome data and are expected to increase following data validation.I

Download the underlying data for Figure 1 as Excel Worksheet

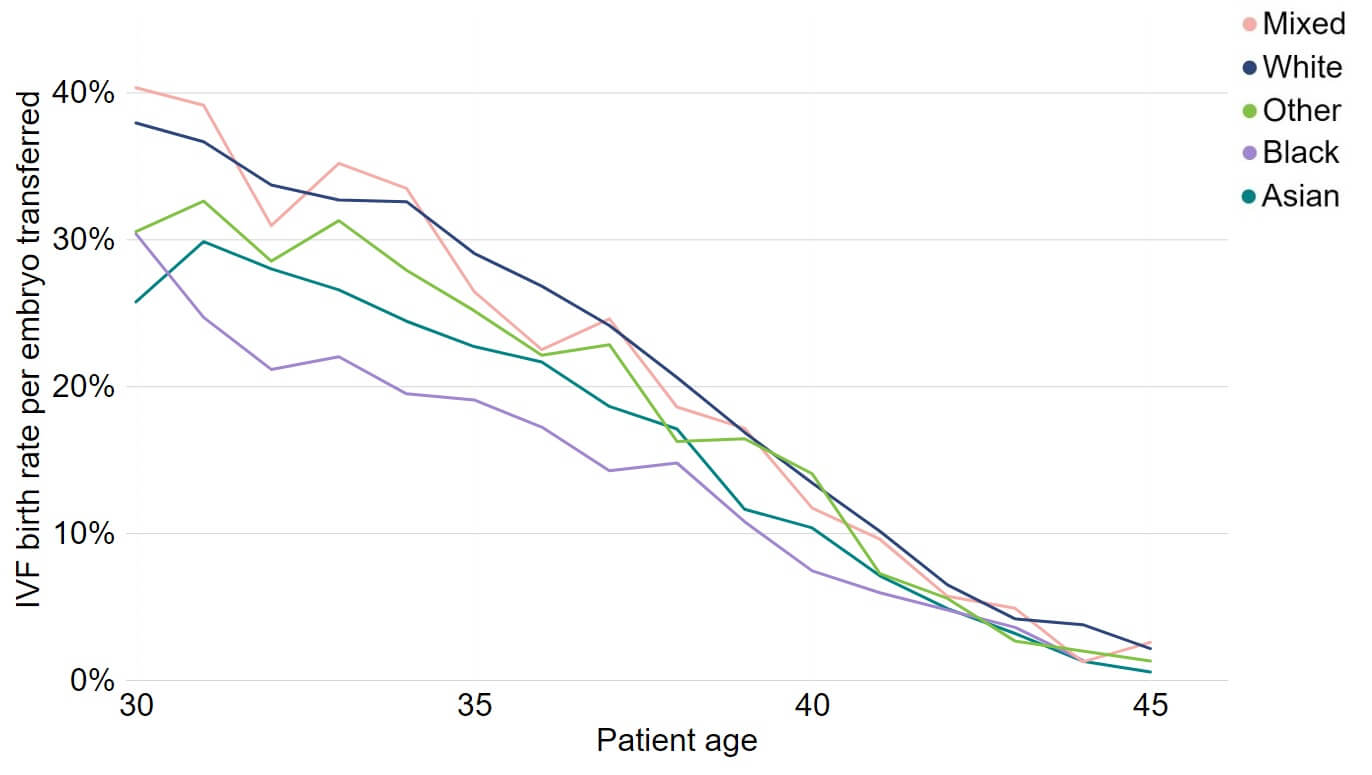

To account for the age differences across ethnic groups, we have compared birth rates by patient age from 2017 to 2021 (Figure 2). Asian and Black patients consistently had lower birth rates per embryo transferred from age 30 to 37, though the differences narrowed above 37.

While all patients experience reduced fertility at older ages, there are ethnic differences in prevalence and causes of infertility. For example, tubal damage, endometriosis and fibroids have been reported as being more common among the Black population.5-8 The evidence is mixed, but some studies suggest prevalence of ovulatory disorders varies by ethnicity.9,10

Ethnic differences in general health may also play some part in observed differences in the birth rates. For example, obesity is associated with not only increased risk of infertility but also impairs ovarian response to stimulation drugs and decreases implantation and live birth rates following IVF.11 Prevalence of obesity in the UK varies by ethnic groups.12 The mechanism of these health disparities is complex and may be influenced by existing social and economic inequalities, pre-existing diseases and other societal factors.13

Figure 2. IVF birth rate lower among Black patients

Average fresh embryo transfer IVF birth rate per embryo transferred using patient eggs by age and ethnicity, 2017-21 (preliminary 2019-21 data)

Note figure 2: Birth rates for 2019, 2020 and 2021 are preliminary and have not been validated. This data includes IVF treatment cycles using their own egg and fresh embryo transfers, and begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. Treatments using PGT-A/M/SR, donor eggs or surrogacy, and treatments in which a pregnancy was recorded and no birth outcome recorded have been excluded.

Download the underlying data for Figure 2 as Excel Worksheet

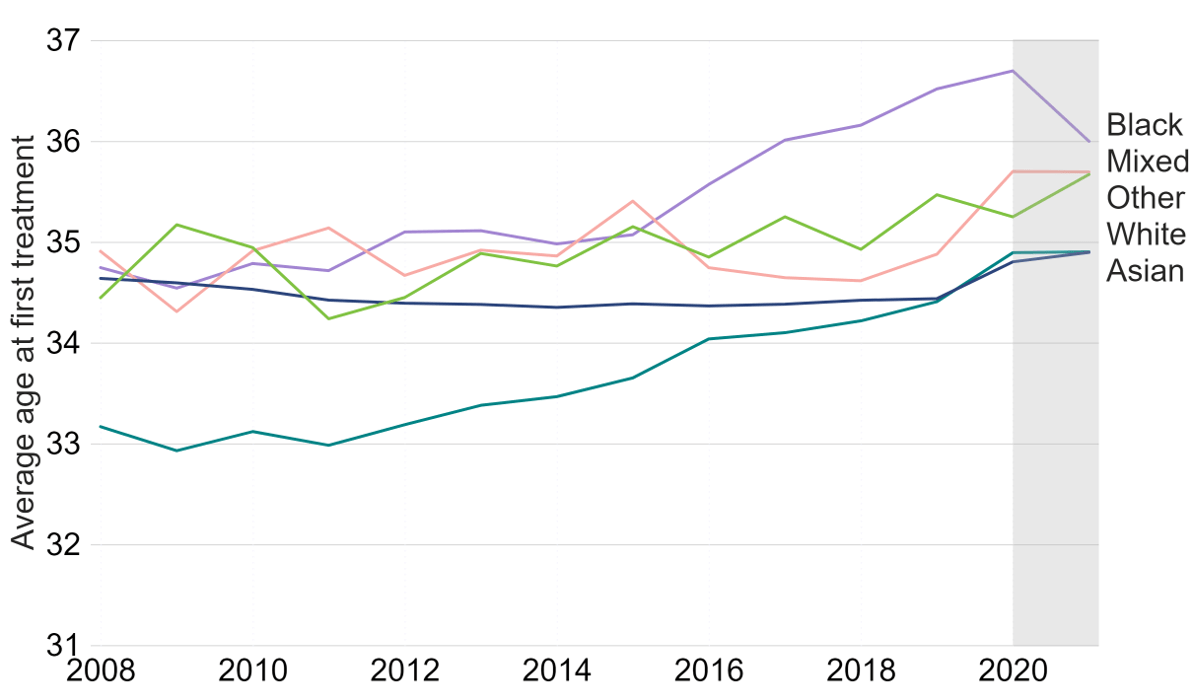

2. Black patients started fertility treatment later than other ethnic groups

The average age of patients in heterosexual relationships having their first treatment in 2021 was 35.0. As shown in Figure 3, this varied by ethnicity. Patients of Mixed, Other and White ethnic groups commonly had their first cycle between 34 and 36 years of age, increasing slightly since 2019. Black patients had the largest increase in age at first treatment from 35.1 in 2015 to 36.0 in 2021. From 2008-19, Asian patients remained the youngest ethnic group starting treatment, although this has steadily increased from below 34 years of age in 2008 to nearly 35 in 2021. Within the Asian ethnicity, Chinese patients tended to be older at 37 years of age in 2021, while Bangladeshi and Pakistani patients were younger at an average age of 33.4 or younger.

Variations in when patients first started fertility treatment may be related to a number of reasons, including availability of treatment, NHS funding, costs, differences in family formations, and fertility awareness.14,15 Ethnic minority groups may also experience delayed treatment of pre-existing causes of infertility.7 The increased average age among Black patients may in part be explained by lack of or limited availability of NHS funding and costs associated with privately funded treatments, see section 8 for differences in NHS-funded cycles.

The rise in average age across most ethnic groups in 2020 may be related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The 2021 National Patient Survey reported that Black, Asian, Mixed or Other ethnicity patients were more likely to have reported a delay in speaking with a GP due to COVID-19 compared to White patients.

Figure 3: Average age at first treatment increased among Black and Asian patients

Average age at first IVF or DI cycle among patients aged 18-49 with male partner, 2008-21 (preliminary 2020-21 data)

Note figure 3: The data is preliminary for 2020 and 2021 and have not been validated. This data includes the average (mean) age of patient’s first IVF or DI cycle begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. Treatments using surrogacy have been excluded. This figure focuses on patients with a male partner as the NHS funding criteria vary by partner type.16

Download the underlying data for Figure 3 as Excel Worksheet

The average age at first treatment for patients in female same-sex partnerships in 2017-21 was younger than patients in heterosexual partnerships at 32.7 years old, ranging from 32.5 for patients with a mixed background and 32.7 for White patients to 35.8 years for Asian patients. Although female same-sex couples may start treatment sooner than heterosexual couples, ethnic differences at the age of first treatment remain and this may be due to varied funding criteria, costs and longer waiting lists for donors of matching ethnicity.17

Single patients had their first treatment later, with average ages of 36.2 for White and 36.8 for patients with a mixed ethnic background in 2017-21. Asian and Black single patients had their treatment latest (38.2 years and 38.5 years, respectively). This may be due to varied funding criteria and costs.

3. DI predominantly used by White patients

The ethnicity of IVF patients was similar to that of a comparable population aged 18-49 in the UK, with some key differences. In 2017-21, IVF was most used by White patients (77%), followed by Asian (15%), Black (3%), Other (4%) and Mixed (2%) patients (Table 1).

Black IVF patients accounted for 3% of IVF patients compared to 4% of the age-matched UK population. Asian patients made up a higher proportion of IVF patients at 15% compared to 11% of the aged-matched population.

DI accounted for 8% of treatment cycles in 2017-21. Most DI patients were White (92%), with the remainder of Asian (3%), Black (2%), Mixed (2%) and Other (1%) ethnicities (Table 1). DI is more commonly used among female same-sex couples and single patients, see section 7 for further information on partner type.

| Table 1: Black populations less commonly used fertility treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of patients aged 18-49 by ethnicity and treatment type, 2017-21 (preliminary 2020-21 data) | |||||

| Asian | Black | Mixed | White | Other | |

| Female population in UK (2021 Census) |

11% | 4% | 3% | 79% | 2% |

| IVF patients | 15% | 3% | 2% | 77% | 4% |

| DI patients | 3% | 2% | 2% | 92% | 1% |

| Note table 1: The data is preliminary for 2020 and 2021 and have not been validated. This includes patients who had at least one cycle in 2017-21 begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. Patients acting as surrogates and patients with no ethnicity data have been excluded from this table. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding. The Census population estimate is calculated using data from the 2021 Census for England and Wales, the 2021 Census for Northern Ireland and the 2011 Census for Scotland. The ethnicity and single age population data from the 2022 Scotland Census has not been released at the time of this publication. The population of Scotland was estimated to make up a similar proportion of the UK population in both 2011 and in 2021 at 8%.18 | |||||

Download the underlying data for Table 1 as Excel Worksheet

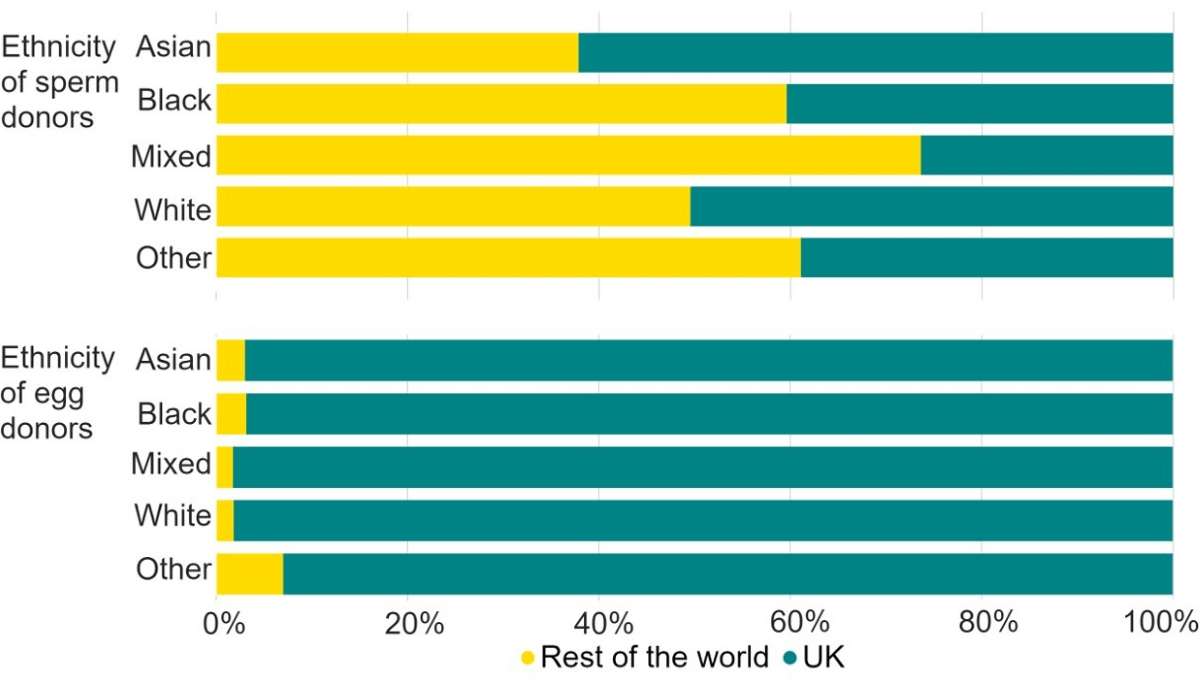

4. Imported donor sperm and eggs vary by ethnicity

Patients requiring donor eggs or sperm may choose to source them from outside of the UK, a trend that has become more common with donor sperm in recent years.19 One reason that patients may import donor sperm or eggs is to find a donor of matching ethnicity. In response to our 2021 National Patient Survey, 82% of respondents said it was important that the ethnicity of a donor matched their own.

About 51% of all cycles using donated sperm in 2017-21 used imported sperm from abroad, whereas only 2% of cycles using donated eggs were from imports. Most Mixed (74%), Other (61%) and Black (60%) ethnicity sperm used in 2017-21 were from imports (Figure 4). In contrast, White and Asian sperm were most commonly from the UK, with 50% and 38% of sperm donations used respectively from imports. This may indicate limited availability of donors in the UK, particularly from Mixed, Other and Black backgrounds.

In contrast, donor eggs used for treatment in 2017-21 were mostly from the UK, with egg donations from donors of Other ethnicities most likely to be imported at 7%, followed by Black and Asian donors at 3%.

Figure 4: Over half of Mixed, Other and Black donor sperm used in IVF treatments were imported from abroad

Proportion of IVF cycles using imported donor sperm and eggs by donor’s ethnicity, 2017-21 (preliminary 2020-21 data)

Note figure 4: Data for 2020 and 2021 is preliminary and has not been validated. This data excludes DI cycles and includes IVF treatment cycles begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use.

Download the underlying data for Figure 4 as Excel Worksheet

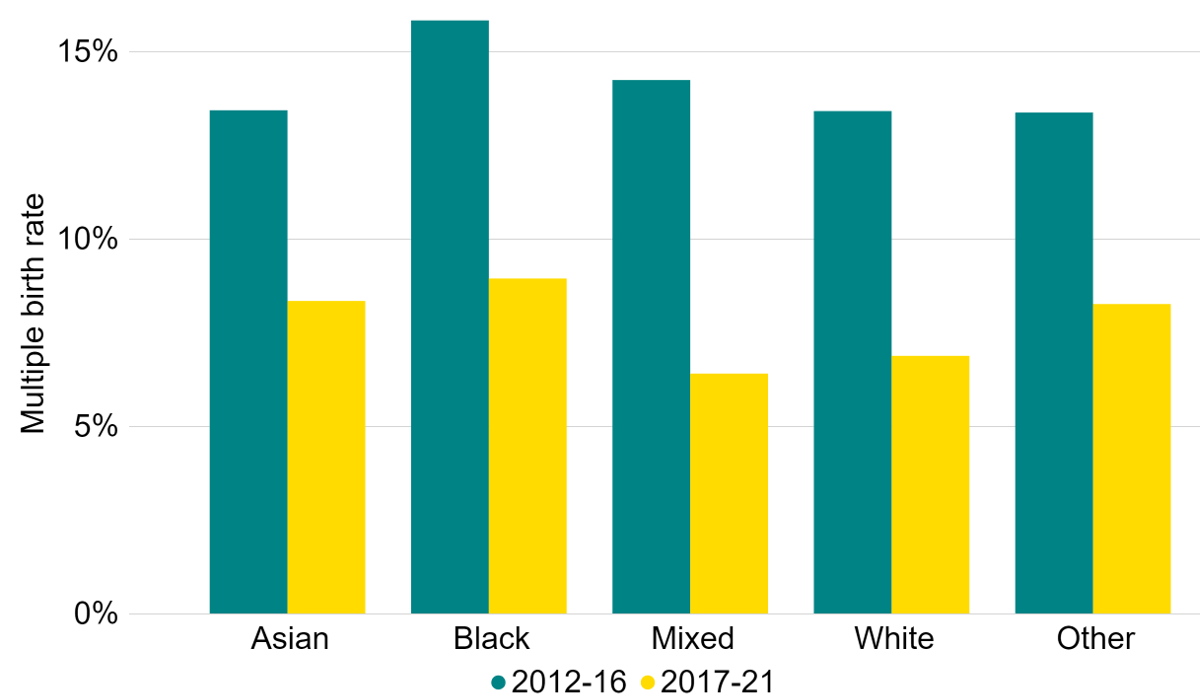

5. Multiple birth rate decreased in all ethnic groups, but remain highest for Black patients

Multiple births cause increased risk of health problems for patients and their babies, such as late miscarriage, gestational diabetes, still birth and neonatal and maternal death.20 In the early 1990s the average UK multiple birth rate from IVF was around 28%. Following the launch of the ‘One at a time’ campaign in 2007 and the introduction of multiple birth rate targets for the sector in 2009, a 10% target was reached in 2017. As a result, multiple birth rates have decreased across the UK to reach a record low of 5% in 2021.21

The multiple birth rate for all ethnic groups declined from 2012-16 to 2017-21, although ethnic differences persist (Figure 5). The multiple birth rate reduced from 16% to 9% for Black patients and from 14% to 6% for patients with a mixed ethnic background.

Professional guidelines advise that clinics recommend single embryo transfer for good prognosis patients (e.g. patients under 37).22-24 However, proportions of patients aged under 37 years old undergoing their first IVF cycle who undertook multiple embryo transfer ranged from 13% for White patients to 20% for Black patients in 2017-21.

In response to our 2021 National Patient Survey, respondents cited advanced age, number of previous unsuccessful IVF cycles, low ovarian reserve and quality of embryos as main reasons for choosing to transfer multiple embryos. Variation in use of multiple embryo transfers across ethnic groups may also relate to financial factors.25,26 See section 8 for more information on funding variation by ethnicity.

Figure 5. Average IVF multiple birth rate decreased in all ethnic groups

IVF average live multiple birth rate among patients aged 18-49 by ethnicity, 2012-16 and 2017-21 (preliminary 2019-21 data)

Note figure 5: Multiple birth rates for 2019, 2020 and 2021 are preliminary and have not been validated. This data includes cycles using either patient or donor eggs and IVF treatment cycles begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. Treatments in which a pregnancy was recorded and no birth outcome recorded have been excluded.

Download the underlying data for Figure 5 as Excel Worksheet

6. Use of egg storage was similar across all ethnic groups

Most patients using fertility services do so with the intention of trying to conceive as soon as possible. However, there are other reasons people may use fertility services, such as freezing eggs, sperm, or embryos so that they can hopefully have a biological family in the future. Egg storage cycles provide an opportunity for patients to preserve fertility for medical reasons or for patients who want to freeze their eggs to have a family later in life. Egg storage is one of the fastest growing fertility treatments in the UK.21

In 2017-21, use of egg storage was similar across ethnic groups, but most used among patients of Other ethnic groups with 5% of all cycles being egg storage, followed by patients with Black and a mixed ethnic background (Table 2). The proportion of all cycles that used egg storage were lowest among White patients at 3%. The average (median) age of egg storage was similar across ethnicity around 36-37 years of age. Reasons for egg storage are not collected in our Register, therefore this data includes both medical and social egg storage cycles.

| Table 2: Use of egg storage cycles was similar across ethnic groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number and percentage of egg storage cycles among all cycles by ethnicity, 2017-21 (preliminary 2020-21 data) | |||

| Number of egg storage cycles |

Number of all cycles |

Egg storage as a percent of all cycles |

|

| Asian | 1,682 | 49,146 | 3% |

| Black | 496 | 11,063 | 4% |

| Mixed | 298 | 7,322 | 4% |

| White | 7,767 | 287,407 | 3% |

| Other | 694 | 13,102 | 5% |

| Total | 10,937 | 368,040 | 3% |

| Note table 2: Data for 2020 and 2021 is preliminary and has not been validated. Data exclude cycles for donation, research and thawing only for embryo biopsy cycles. Egg storage cycle data includes cycles that intended to store patient eggs only. Reasons for egg storage are not collected, therefore this data includes both medical and social egg storage cycles. Classification of egg storage cycles has changed, see Quality and Methodology report, and cannot be directly compared to previous reports. | |||

Download the underlying data for Table 2 as Excel Worksheet

7. Higher proportions of Black patients were single

In 2021, IVF treatments were mostly used by patients with a male partner (90%), while DI treatments were more commonly used by patients in female same-sex relationships (44%).21 As seen in Table 3, family types vary by ethnic group.

Asian patients more commonly had a male partner for both IVF and DI treatment than other ethnic groups in 2017-21 (98% of IVF treatments, 45% of DI treatments). Asian patients were least commonly in female same-sex couples or single.

Higher proportions of Black IVF and DI patients were single compared to other ethnic groups in 2017-21 (6% IVF, 62% DI). Lastly, White patients had the highest proportion of patients with a female partner (5% IVF, 48% DI), followed by patients with a mixed ethnic background (4% IVF, 42% DI). This is similar to findings from the 2021 Census for England and Wales, where sexual orientation was most varied among respondents of White or mixed ethnic backgrounds.27

There were 941 surrogates who had treatment in 2017-21. Of the 839 who provided their ethnicity, 90% were White with the remainder of Asian (3%), Black (3%), Mixed (2%) and Other (3%) ethnic groups.

| Table 3: Higher proportion of Black, Mixed and White IVF patients were single | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of patients by ethnicity and partner type, 2017-21 (preliminary 2020-21 data) | |||||

| Treatment | Ethnic group | Number of patients |

Partner type | ||

| Male partner | Female partner | No partner | |||

| IVF | Asian | 21,842 | 98% | <1% | 2% |

| Black | 4,786 | 93% | 1% | 6% | |

| Mixed | 3,019 | 90% | 4% | 6% | |

| White | 114,714 | 91% | 5% | 5% | |

| Other | 5,297 | 96% | 1% | 3% | |

| DI | Asian | 323 | 45% | 15% | 41% |

| Black | 233 | 20% | 18% | 62% | |

| Mixed | 229 | 14% | 42% | 44% | |

| White | 9,946 | 15% | 48% | 38% | |

| Other | 146 | 23% | 17% | 60% | |

| Note table 3: Data for 2020 and 2021 is preliminary and has not been validated. Treatment cycles include cycles begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding. | |||||

Download the underlying data for Table 3 as Excel Worksheet

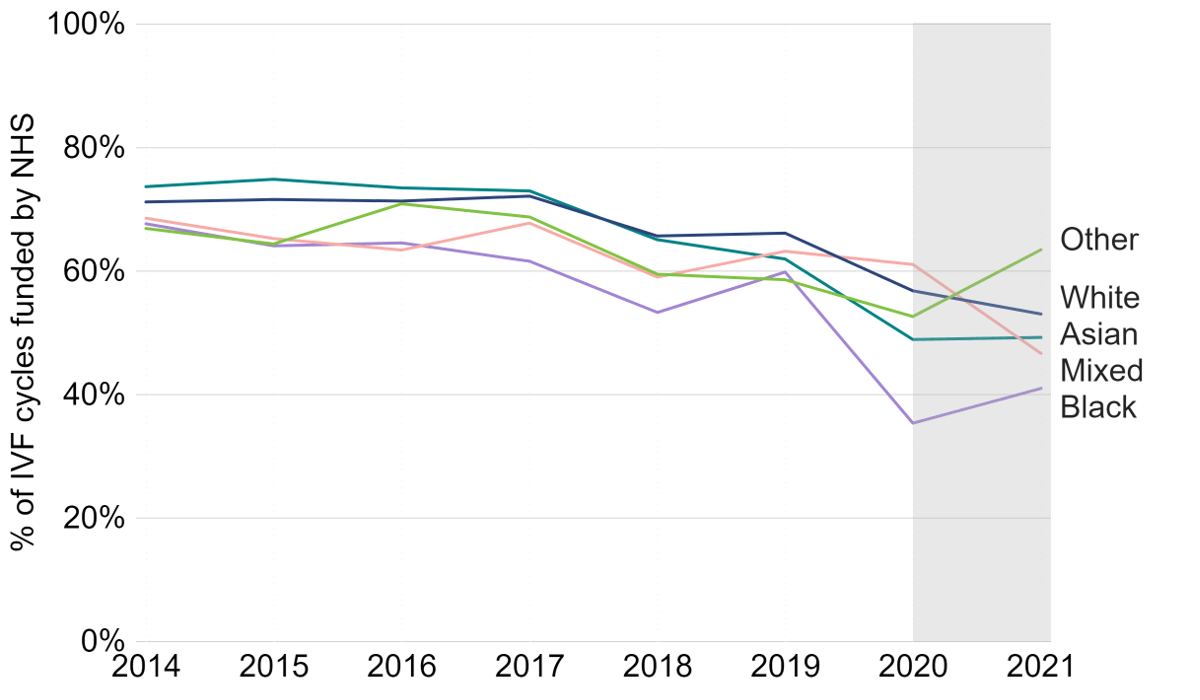

8. NHS-funded IVF cycles declined most among Black patients

NHS-funded IVF cycles across the UK have declined in recent years, although the rate of decline varied by nation and English region.21 The overall percentage of NHS-funded IVF cycle among patients under 40 in heterosexual relationships declined from 71% in 2014 to 52% in 2021 (Figure 6). All ethnic groups have seen a decrease in the percent of NHS-funded IVF cycles, but disparities between ethnic groups have widened.

NHS-funded IVF cycles decreased most among Black patients in recent years, from 60% in 2019 to 41% in 2021. In 2021, the proportion of IVF cycles funded through the NHS was 47% for Mixed, 49% for Asian, 53% for White, and 63% for Other patients.

These differences likely relate to regional funding availability and eligibility criteria set by the devolved governments in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) in England. Availability of IVF funding can range from no funding to three funded cycles depending on location and eligibility restrictions such as body mass index (BMI) applied.16 Prevalence of obesity in the UK varies by ethnic groups,12 which may have some impact on accessing available funding.

The decline in NHS-funded IVF cycles from 2019 to 2020 may partly be explained by difficulty in accessing treatment or delays in accessing tests or surgeries prior to starting treatment due to the COVID-19 pandemic.28 The decrease in NHS-funded IVF cycles among Black patients likely relates to changes to funding criteria or access to treatment in London where 49% of the Black population in England and Wales lived in 2021.29 NHS-funded treatments decreased most in London from 23% in 2019 to 17% in 2021.21

NHS-funding for IVF has been more limited among patients in female same-sex relationships and single patients.30,31 Female same-sex couples are often eligible for NHS-funded IVF only after completing 6-12 privately funded DI cycles.16 In 2017-21, 12% of patients in female same-sex relationships under 40 with no previous live birth received NHS-funded DI or IVF cycles in the UK, ranging from 16% for patients with Other background, 12% for White and Asian patients to 6% for patients with a mixed background. For single patients, 9% of IVF or DI cycles were NHS-funded, ranging from 10% for Other, 9% for White to 7% for Asian patients. See section 2 for differences in average age at first treatment.

Figure 6: NHS-funded IVF cycles declined most among Black patients

Percentage of IVF cycles funded by NHS among patients aged 18-39 with a male partner, first IVF cycles and no previous live birth, United Kingdom (preliminary 2020-21 data)

Notes figure 6: Data for 2020 and 2021 is preliminary and has not been validated. This data includes both fresh and frozen embryo transfers, and patient’s first IVF treatment cycles begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. This figure focuses on patients with male partner on their first IVF cycle with no previous live births as funding criteria vary by partner type, as well as number of previous cycles and children.16

Download the underlying data for Figure 6 as Excel Worksheet

Conclusion and next steps

When we published our first report in 2021 we raised a series of actions for the HFEA and others in response to the findings. Some of these actions included: seeking views from patients of ethnic minority backgrounds on their experiences in UK clinics through our National Patient Survey 2021, holding in-depth workshops with clinic staff on where tangible actions should be targeted in reducing disparities, and publishing increased information from our Register on ethnicity to improve transparency and enable further research on ethnic differences. For a more detailed outline of the actions we have taken, please see the Authority paper here.

However, the data in this report shows that there is still much to be done. To further this work, the HFEA, British Fertility Society, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and Fertility Network UK have agreed a call to action to reduce disparities in access to and outcomes for Black, Asian and ethnic minority patients.

“We call for action to ensure that Black, Asian and ethnic minority patients and their partners are not left behind in access to and experience of fertility treatment. Fertility treatment can be extremely stressful and expensive, and the changes we are calling for aim to reduce disparities in access to and outcomes for Black, Asian and ethnic minority patients.

Our call is for improvements to be made to development of clinical policy, information and awareness, NHS commissioning, and research to tackle the ethnic disparities in fertility treatment.”

The full call to action is available here.

About our data

This report uses preliminary treatment and pregnancy data for 2020-21 and preliminary birth outcome data for 2019-21. This is because the HFEA has recently launched a new data submission system for licensed clinics and migrated our fertility treatment and outcomes data to a new database. This data migration has resulted in delays which has prevented the validation of the 2020-21 treatment and pregnancy data and 2019-21 birth outcome data. Data validation involves data quality checks that verify treatment, pregnancy and birth outcome data.

This report covers the period from 2008-21 where data is available. The information that we publish is a snapshot of data provided to us by licensed clinics. The figures supplied in this report are from our data warehouse containing Register data as of 19 April 2023. The data on donor’s ethnicity in Figure 4 are from our data up to September 2021. Results are published according to the year in which the cycle was started. For further information, please see our Quality and Methodology report.

Unless stated otherwise, the data in this report refers to treatment cycles i.e. only those cycles where the patient recorded on their registration form that they intended to have immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use.

About the HFEA

The HFEA is the UK’s independent regulator of fertility treatment and research using human embryos. Set up in 1990 by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, the HFEA is responsible for licensing, monitoring, and inspecting fertility clinics and research centres – and taking enforcement action where necessary – to ensure everyone accessing fertility treatment receives high quality care.

The HFEA is an ‘arm’s length body’ of the Department for Health and Social Care, working independently from Government providing free, clear, and impartial information about fertility treatment, clinics and egg, sperm, and embryo donation.

The HFEA collects and verifies data on all treatments that take place in UK licensed clinics which can support scientific developments and research and service planning and delivery.

The HFEA is funded by licence fees, IVF treatment fees and a grant from UK central government. For more information visit, hfea.gov.uk.

Contact us regarding this publication

Media: press.office@hfea.gov.uk

Statistical: intelligenceteam@hfea.gov.uk

Accessibility: comms@hfea.gov.uk

Footnotes

- Data validation involves quality checking data submitted from licensed clinics across the UK to verify that treatment, pregnancy and birth outcome data are correctly recorded on our data Register.

Notes on Ethnic diversity in fertility treatment

- Race Disparity Unit Cabinet Office. List of ethnic groups.

- Wellons, M. F. et al. Race matters: a systematic review of racial/ethnic disparity in Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology reported outcomes. Fertil Steril 98, 406–409 (2012).

- Maalouf, W., Maalouf, W., Campbell, B. & Jayaprakasan, K. Effect of ethnicity on live birth rates after in vitro fertilisation/intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatment: analysis of UK national database. BJOG 124, 904–910 (2017).

- Huttler, A. & Thornton, K. L. The complexity of addressing racial and ethnic disparities. Fertil Steril (2023).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). Ethnic diversity in fertility treatment 2018. (2021).

- Day Baird, D., Dunson, D. B., Hill, M. C., Cousins, D. & Schectman, J. M. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: Ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188, 100–107 (2003).

- Bougie, O., I Yap, M., Sikora, L., Flaxman, T. & Singh, S. Influence of race/ethnicity on prevalence and presentation of endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 126, 1104–1115 (2019).

- Seifer, D. B., Frazier, L. M. & Grainger, D. A. Disparity in assisted reproductive technologies outcomes in black women compared with white women. Fertil Steril 90, 1701–1710 (2008).

- VanHise, K. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 119, 348–354 (2023).

- Ding, T. et al. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in reproductive-aged women of different ethnicity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 8, 96351–96358 (2017).

- Luke, B. Adverse effects of female obesity and interaction with race on reproductive potential. Fertil Steril 107, 868–877 (2017).

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Overweight adults (2023).

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Health disparities and health inequalities: applying All Our Health (2022).

- Berrington, A. Expectations for family transitions in young adulthood among the UK second generation. J Ethn Migr Stud 46, 913–935 (2020).

- Gameiro, S., El Refaie, E., de Guevara, B. B. & Payson, A. Women from diverse minority ethnic or religious backgrounds desire more infertility education and more culturally and personally sensitive fertility care. Human Reproduction 34, 1735–1745 (2019).

- Department of Health and Social Care. NHS-funded in vitro fertilisation (IVF) in England (2023).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). National Patient Survey 2021 (2022).

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Population estimates for the UK, England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: mid-2021. (2022).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). Trends in egg, sperm and embryo donation 2020. (2022).

- Santana, D. S. et al. Perinatal outcomes in twin pregnancies complicated by maternal morbidity: evidence from the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 449 (2018).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). Fertility treatment 2021: preliminary trends and figures (2023).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Fertility problems: assessment and treatment (2017).

- Harbottle, S., Hughes, Ci., Cutting, R., Roberts, S. & Brison, D. Elective Single Embryo Transfer: an update to UK Best Practice Guidelines. Hum Fertil 18, 165–183 (2015).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Code of Practice 9th edition (2023).

- Fertility Network UK. The impact of the cost-of-living crisis on UK fertility patients (2023).

- Chambers, G. M. et al. The impact of consumer affordability on access to assisted reproductive technologies and embryo transfer practices: an international analysis. Fertil Steril 101, 191-198.e4 (2014).

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Sexual orientation, further personal characteristics, England and Wales: Census 2021 (2023).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). Impact of COVID-19 on fertility treatment 2020 (2022).

- Race Disparity Unit Cabinet Office. Regional ethnic diversity (2022).

- Department of Health and Social Care. Women’s Health Strategy for England (2022).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). Family formations in fertility treatment 2018 (2020).

Review date: 1 February 2026